In the world of Health, Safety, and Environment (HSE), we are constantly striving to make workplaces safer. We put up guardrails, write procedures, conduct training, and install complex safety systems. But a fundamental question always arises: How safe is safe enough?

Is it possible to eliminate every single risk? No. In any industrial process, from chemical manufacturing to construction, residual risk will always remain. So, where do we draw the line? When can we confidently say we have done enough?

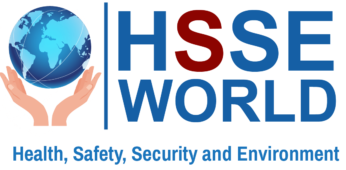

This is where the concept of ALARP comes in. ALARP stands for “As Low As Reasonably Practicable.” It is a cornerstone of health and safety law and risk management, particularly in the UK and many other countries following similar legal frameworks.

This blog post will provide a comprehensive, practical guide to understanding and working with the ALARP principle. We will break down its legal origins, what it truly means, and how you can apply it in your organization to make defensible, ethical, and effective safety decisions. We aren’t just going to define it; we are going to explore how to get there.

What is the ALARP Principle?

At its core, the ALARP principle is about balance. It involves weighing the cost—in terms of time, money, and effort—of reducing a risk against the benefit of that risk reduction.

The concept originated from a landmark 1949 English court case, Edwards v. The National Coal Board. In this case, the court established that safety measures must be considered in the context of the risk they are designed to mitigate. The ruling positioned that:

“… in every case, it is the risk that has to be weighed against the measures necessary to eliminate the risk.”

This simple statement forms the bedrock of modern safety law. It moves away from the idea of “absolute safety” (which is impossible) and towards a pragmatic approach of “reasonable safety.”

What ALARP is NOT (Common Misconceptions)

Before diving into the “how,” it is crucial to understand what ALARP does not mean. Many people misinterpret the phrase, leading to poor safety decisions or legal non-compliance.

- It is not “As Low As Possible” or Zero Risk: ALARP does not mean eliminating every trace of risk. If you run a logistics company, the risk of a vehicle accident is never zero. ALARP acknowledges this reality.

- It is not just “Physically Possible”: Just because you can bolt on an extra safety system doesn’t mean you must. The measure must be “reasonably practicable,” not just theoretically possible.

- “Tolerable” does not mean “Acceptable”: This is a critical distinction from the UK Health and Safety Executive’s (HSE) guidance (R2P2 – Reducing Risk, Protecting People). A “tolerable” risk is one that society is willing to live with to secure certain benefits (like jobs or energy), in the confidence that it is being properly controlled. It does not mean that everyone would agree to take the risk voluntarily.

Why is ALARP Required?

You cannot ignore ALARP. It is embedded in the fabric of modern HSE management for several reasons:

- Legal Requirement: It is explicitly required by regulations such as the UK’s Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974. If you are found to have a risk that is not reduced to a level that is “reasonably practicable,” you can be held liable for negligence or breach of duty.

- Consensus Standards: While not always stated in these exact words, management system standards like ISO 45001 infer the need to reduce risks to a level that is as low as practicable.

- Industry and Stakeholder Expectation: NGOs, insurers, and industry bodies expect organizations to demonstrate they have considered risk reduction diligently. Failing to do so can impact your insurance premiums, your reputation, and your social license to operate.

- Good Business Sense: Reducing risk prevents accidents, which saves money, protects your workforce, and ensures business continuity.

The Core Definition: “Grossly Disproportionate”

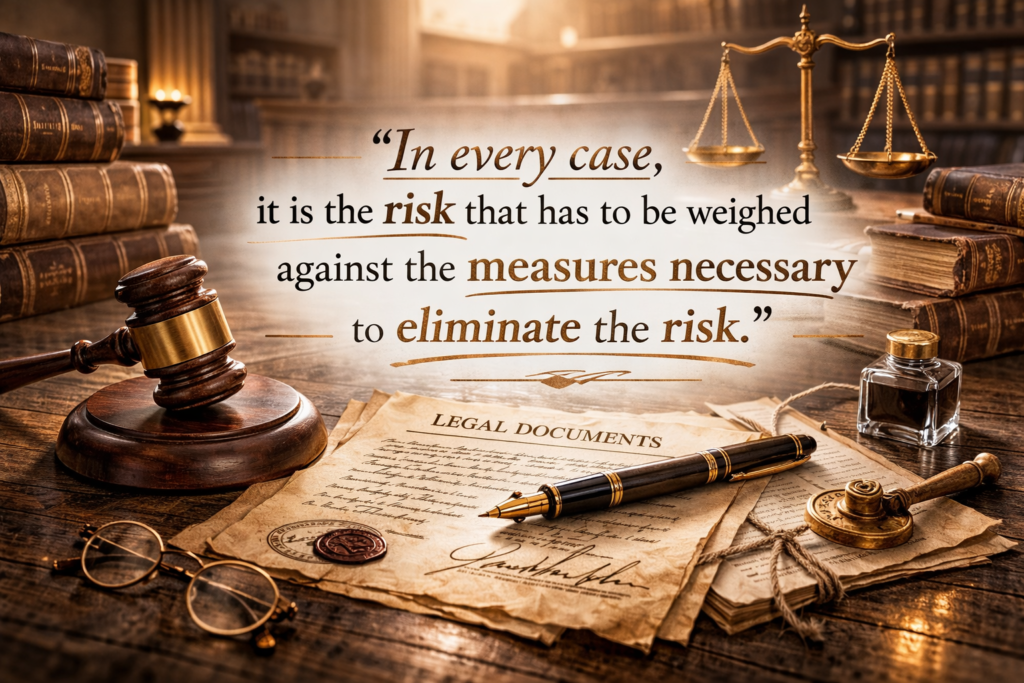

The industry-wide accepted definition of ALARP hinges on one key phrase: “Grossly Disproportionate.”

A risk is considered to be reduced to ALARP when the cost (financial, time, effort) required to implement any further or incremental risk reduction measure is grossly disproportionate to the amount of risk being reduced.

Think of it as a tipping point. Early safety measures (e.g., a basic guard on a machine) provide a huge reduction in risk for a small cost. As you add more and more layers of protection (e.g., advanced laser sensors, dual-redundant control systems, AI monitoring), the amount of risk you reduce with each new layer gets smaller, while the cost of that layer gets higher.

At a certain point, spending another $1 million might only make the risk 0.0001% safer. That cost is “grossly disproportionate” to the benefit, and you have likely reached an ALARP level.

How to Determine if You Are at ALARP: A Step-by-Step Conceptual Approach

There is no single formula or algorithm to calculate ALARP. It is a judgment-based process, but it must be an informed and documented judgment. Here is a practical, step-by-step approach inspired by the concepts in the provided document.

Step 1: Assess the Hazard and Baseline Risk

You cannot manage what you don’t measure. Start by defining a specific scenario.

- Hazard: What is the source of potential harm? (e.g., Naphtha, high voltage electricity, working at height).

- Adverse Event: What could go wrong? (e.g., Loss of containment—overflow of a vessel).

- Consequence: What would the result be? (e.g., Ignition of vapors leading to fire, injuries, and asset damage).

- Baseline Risk: How often might this happen without any specific barriers in place? Use plant experience, industry data, and equipment performance data to estimate a frequency (e.g., once in every 1000 vessel fillings, or 1 x 10<sup>-2</sup> per filling).

Step 2: Identify and Analyze Your Existing Barriers (The “Bare Min”)

Now, look at what you already have in place to prevent that event. These are your safety barriers, safeguards, or layers of protection. For our naphtha overflow scenario, the bare minimum barriers might be:

- Administrative: An operator walkabout to visually check for overflow, a procedure to take ullage (measure empty space) before filling, and a logbook to record levels.

- Passive/Active: A glass level gauge so the operator can see the level.

These basic barriers provide an initial level of risk reduction. Let’s say, for the sake of this conceptual model, that they reduce the risk by one order of magnitude (e.g., from 1×10<sup>-2</sup> to 1×10<sup>-3</sup>).

Step 3: Add Barriers to Meet Minimum Standards (The “Tolerable” Level)

Your existing barriers might not be enough. You likely need to meet specific legal requirements, industry standards (like RAGAGEP – Recognized and Generally Accepted Good Engineering Practices), and your own internal company standards.

To comply with these, you might need to add more robust, engineered barriers. In our example, this could include:

- Hydrostatic Devices: Displacers, Bubblers.

- Continuous Monitoring: Continuous Float Level Transmitters.

These are not just “nice to haves”; they are installed to manage legal liabilities and meet basic safety expectations. These additional barriers might further reduce the risk by another order of magnitude (now from 1×10<sup>-3</sup> to 1×10<sup>-4</sup>).

Step 4: Go Beyond Compliance to Reach “Tolerable Risk”

Even with legal compliance, your organization might define a specific “Tolerable Risk” target. This is a quantitative threshold you want to meet. To reach this, you might add even more standard industry technology, such as:

- Magnetic Level Gauges

- Load Cells (to weigh the vessel)

These are often installed because they are reliable, well-understood, and help you meet a recognized safety benchmark. This might bring your risk down to the “Tolerable” level, say 1 x 10<sup>-5</sup>.

Important Note: You must be at a “Tolerable Risk” level before you can even begin to argue that you are at ALARP. ALARP starts where compliance and tolerability end.

Step 5: The ALARP Test – Analyzing Further Risk Reduction

This is the critical step. Now that you are at a tolerable level, you ask: “Should we add more?”

You look at the next tier of advanced technology. For our tank overflow, this could be:

- Capacitance Transmitters

- Ultrasonic Liquid Level Sensors

- Laser Level Transmitters

These are sophisticated, expensive, and provide a very small increment of additional safety. You now perform the “grossly disproportionate” test.

- Incremental Risk Reduction: How much safer will we be? In our example, adding these three new systems might only reduce the risk by a tiny fraction (e.g., from 1 x 10<sup>-5</sup> to 0.9 x 10<sup>-5</sup>, or an additional reduction of only 0.1 x 10<sup>-6</sup>).

- Cost: What is the total cost of these new systems? This isn’t just the purchase price. “Cost” includes:

- Capital expenditure (buying the equipment)

- Installation expenses (labor, downtime)

- Ongoing maintenance and energy consumption

- Training for operators and technicians

- Increased system complexity (which can sometimes introduce new risks)

If the cost of implementing these new, high-tech sensors is $100,000, and the risk reduction they offer is minuscule, that cost is very likely grossly disproportionate to the benefit.

Step 6: The ALARP Declaration

You have now documented the following:

- Your baseline risk.

- The barriers installed to meet legal and tolerable standards.

- The cost and benefit of potential additional barriers.

- Your reasoned judgment that the cost of further measures is grossly disproportionate to the benefit.

At this point, conceptually, you can state that the risk for this specific scenario has been reduced As Low As Reasonably Practicable.

The “Human” Element: Subjectivity and Judgment

The word “reasonable” makes ALARP fundamentally subjective. What is reasonable to a manager in a remote office might be terrifying to the operator on the ground. Terms like “Grossly Disproportionate” and “Tolerable Risk” suffer from the same difficulty.

This is why the process must be documented. Your safety case is not just about the final decision; it is about the journey you took to get there. It shows that you considered the perspective of the workers, consulted with experts, and made a balanced, ethical decision. Involving the people who do the job (the operators) in this analysis is crucial for both accuracy and buy-in.

Crucial Caveats: ALARP is Not a “Set and Forget” Concept

Reaching ALARP is not the end of the story. It is a point in time. Several factors require you to revisit your ALARP assessments:

- Management of Change (MoC): If you change your process, equipment, materials, or even your staffing levels, the risk profile changes. A change that seems minor (e.g., a new type of gasket) could have a significant impact. Your Management of Change process must trigger a review of the relevant ALARP assessments.

- Technological Advancement: Just because a measure wasn’t reasonably practicable five years ago doesn’t mean it isn’t today. Technology develops, and what was once experimental and expensive can become standard and affordable. You must periodically review new risk control methods to see if they should now be considered “reasonably practicable.”

- Industry Standards Evolve: If a few leading organizations adopt a very high standard, that does not automatically make it ALARP for everyone. ALARP is context-specific. However, if a standard becomes widespread and accepted as “good practice” across the industry, it may eventually become the benchmark for what is “reasonably practicable.”

- Learning from Incidents: If you have an incident or a near-miss, it provides real-world data that may challenge your previous assumptions about risk frequency or consequence. This new information necessitates a review.

- Zero Risk is Impossible: Finally, remember that ALARP does not equal zero accidents. If your risk is truly ALARP, you have done what is reasonably practicable to prevent harm. However, due to the nature of complex systems, the residual risk may still be realized. This does not mean your ALARP judgment was wrong, but it does mean you should investigate the event to see if your assumptions need updating.

Read: Importance of Crane Load Chart

A Word on Methodology: Beyond the Conceptual

The steps outlined in this post are a conceptual guide. A full, robust ALARP determination for a complex facility would require a more detailed methodology, including:

- Quantifying Risk Reduction: How do you determine the “order of magnitude” of risk reduction a barrier provides? This often involves techniques like Layers of Protection Analysis (LOPA) or Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA).

- Defining Costs Precisely: What is the full lifecycle cost of a new safety system?

- Barrier Integrity: What constitutes a valid, independent, and auditable barrier? A procedure is only as good as the person following it; an electronic sensor must have a proven reliability (Safety Integrity Level).

For complex decisions, you should consult with risk specialists and use established risk assessment techniques. This conceptual model helps you think about ALARP, but you need the right tools to prove it.

Conclusion: The Path to Defensible Safety

Working with the ALARP concept is the hallmark of a mature safety culture. It moves you away from a tick-box compliance mentality (“We have done everything the law says”) to a risk-based, ethical decision-making process (“We have done everything reasonable to keep our people safe”).

By following a structured approach—assessing the risk, implementing barriers to meet legal and tolerable standards, and then rigorously testing any further measures against the “grossly disproportionate” criterion—you can make defensible decisions.

You are not just buying safety systems; you are building a safety case. You are demonstrating to your workers, your shareholders, your insurers, and the law that you have acted with diligence, care, and reason.

ALARP is not about finding an excuse to stop spending money on safety. It is about focusing your finite resources on the measures that provide the greatest benefit, ensuring that you aren’t wasting money on expensive “gold-plating” while ignoring more significant risks elsewhere. It is about being safe, smart, and defensible.