Designing office buildings for safety and health is crucial for creating a workplace that promotes the well-being of employees and visitors. A well-designed office building can help to prevent accidents and injuries, reduce the risk of illness, and improve indoor air quality and overall comfort. When designing an office building for safety and health, there are a number of factors to consider, such as adequate ventilation, sanitation and hygiene, social distancing, emergency preparedness, accessibility, mindful material selection, and health and wellness. By considering these and other factors, you can create a space that promotes employee well-being and productivity while also minimizing the risk of accidents, injuries, or illness.

In this context, it is important to understand the most current guidelines and regulations for designing office buildings in your region or country. This may include local building codes, health and safety regulations, and environmental standards. By staying up-to-date on these guidelines, you can ensure that your office building is designed to meet the highest safety and health standards possible.

Also Read: Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs) in the Prep Kitchen

ARCHITECT’S DESIGN

The architect must design the office building with such items as adequate:

- Exits.

- Stairs.

- Ventilation.

- Sanitary facilities.

- Space for the proposed population of workers.

- Lighting and emergency lighting.

- Fire suppression systems.

- Fire-pull boxes.

- Fire alarm system.

- Electrical service

- Security system.

- Processing space.

- Storage space.

Besides being designed to meet safety and health concerns, a building’s layout should work for the occupants, staff, and visitors. It is interesting to note that many factors need to be viewed from a safety and health perspective in order to accomplish a safe and healthy office building. In the following subsections, a few of these are discussed.

Exits and Entries

Provide as many private, ground-level entries to individual units as possible. Ensure that all building entries are prominent and visible and create a sense that the user is transitioning from a public to a semi-private area. Avoid side entries and those that are not visually defined. At all entries consider issues of shelter, security, lighting, durability, and identity as prime considerations (see Figure 1-1). Allow visual access to stairs and elevators from the lobby that will be more protective for those using them. For buildings with clustered and individual unit entries, consider providing small “porch” areas that the company or workers can personalize with signs or greetings, etc. Limit “shared entries” as much as possible since they create a security issue. Consider providing some form of storage for bicycles and other personal items at or close to all main entries.

Also Read: Prevent Office Injuries(Opens in a new browser tab)

Central Facilities and Common Rooms

Consider locating central facilities such as lunchrooms and meeting rooms in a central part of the office building. Common rooms should be linked to common outdoor space. Ensure that these types of rooms are comfortable, accessible, durable, and, most importantly, flexible places. By being centrally located, better security can be maintained for offices clustered around them. These types of rooms should have access to restrooms, a kitchenette, telephone, and should have good storage for audio-visual equipment, etc. Provide as much access to daylight and natural ventilation in all common rooms as possible (see Figure 1-2).

Support and Service Areas

Carefully consider the design and location of key support/service areas such as the building manager’s office, security office, maintenance rooms, janitor’s facilities, mechanical equipment rooms, and trash collection areas. Provide access to bathrooms and kitchens, adequate space, quality furniture, and extra storage this is always an issue in an office building regarding housekeeping and proper storage for each of these uses, together with access to bathrooms and kitchens. Planning of these spaces must be accomplished so that adequate space is part of the design. The manager’s office should supervise the main entrance and should be located centrally, next to operational areas, e.g., security and maintenance rooms. Provide screened trash collection areas that are convenient and easy to access by all occupants. Con- sider the path of travel of trash from the source to the removal area. This can become a hygiene problem as well as a housekeeping issue.

Stairs and Stairways

Ensure stairs are durable, attractive, and safe. Avoid treating stairs as an afterthought. Instead, consider them, particularly entry stairs, as major design elements. Consider how they relate to the street and neighborhood, how they accommodate users and visitors, and what they “say” about the project and its occupants. Consider how the area under the stairs will look and be used. Ensure that all stairs can accommodate moving furniture without damage to finishes (see Figure 1-3). Stairs should have a landing approximately every 12 feet and should be wide enough to provide a minimum of 44 inches. It is critical that variations in riser height, or tread depth not vary over 1/4 of an inch. Variation in these two factors to any degree even for one step will lead to numerous accidents (falls primarily).

All handrails and stair rails should not be less than 36 inches high. If stairs are very wide, a third rail in the center of the stairway provides an element of safety.

It is best if all doors entering and leaving a stairway open are in the way of downward travel for emergency evacuations. All doors should have a panic bar opening mechanism and absolutely no locks of any kind. Stairs that are used for evacuation should open directly onto open areas or onto the street.

Elevators

Locate elevators in sight of the manager’s office or security station if possible. Design elevators so that access to them is in a dead-ended corridor with entry and egress only through the lobby. Design adequate space in front of the elevator to allow waiting and passage. Passenger safety is discussed in the safety portion of this book (see Figure 1-4).

Access Corridors

Corridors should not be less than 44 inches wide. Access corridors should not be of excessive length: i.e., no greater than 100 feet unbroken length. Break up long corridors with lobbies, lighting, benches, materials, color changes, offsets, or artwork. To the best extent possible, provide corridors with access to natural daylight and ventilation. Ensure that all corridors can accommodate moving furniture without damage to finishes. Make sure that corridors that provide a route of escape do not have any design impediments.

Electricity

Strategically placed and an adequate number of electrical outlets to service all offices and office spaces should be available in today’s office environment. This will help prevent the use of extension cords, overloading receptacles, and wires from becoming tripping and fire hazards. By designing office space and cubicles and their furnishings prior to installation of electrical service, you will mitigate many of the issues faced in securing electricity to operate the modern offices of today in a safe manner.

Lighting

In modern offices, illuminance levels are commonly in the range of 10 to 100-foot candles. Good lighting depends on more than just illuminance levels. The direction, distribution, color, and color-rendering index are all sources that contribute to effective lighting (visibility). Illumination levels are generally dictated by the needs of the visual task. Typically, the more light available, the easier it is to perform a specific task. How much light is enough depends upon many factors:

- Details of the task.

- Reflection and contrast (task and background).

- The eye (age and condition).

- Importance of speed and accuracy.

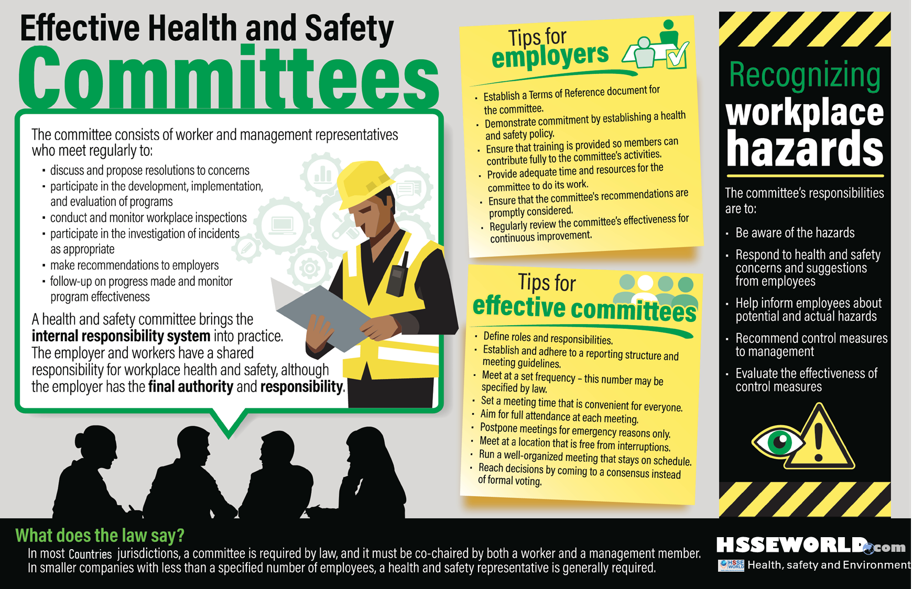

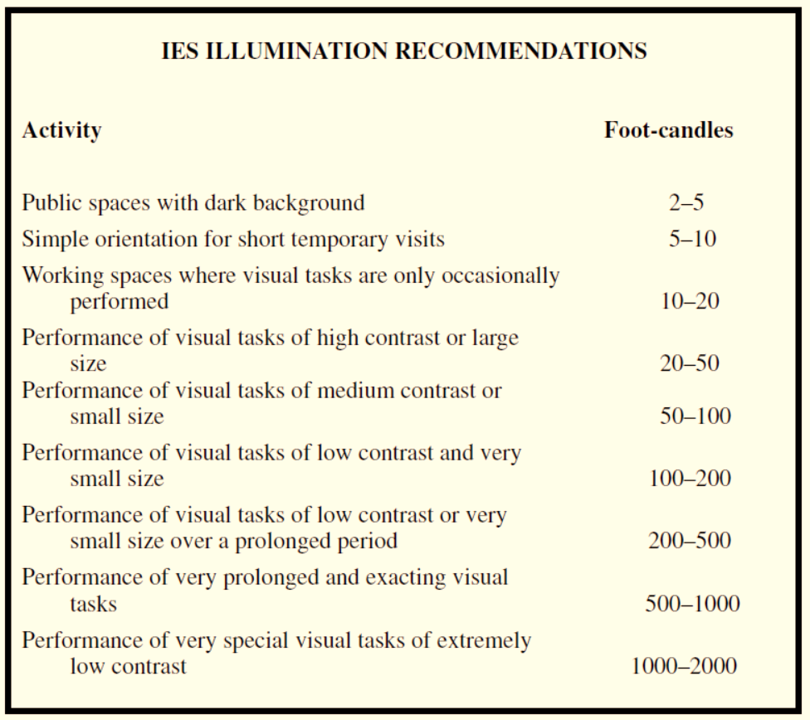

The Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) has published levels of illumination that are deemed appropriate for certain tasks. Examples of recommended levels can be found in Figure 1-5.

Proper workplace lighting is essential to any good business:

- It allows employees to see comfortably what they’re doing without straining their eyes or their bodies.

- It makes work easier and more productive.

- It draws attention to hazardous operations and equipment.

- It helps prevent costly errors and accidents.

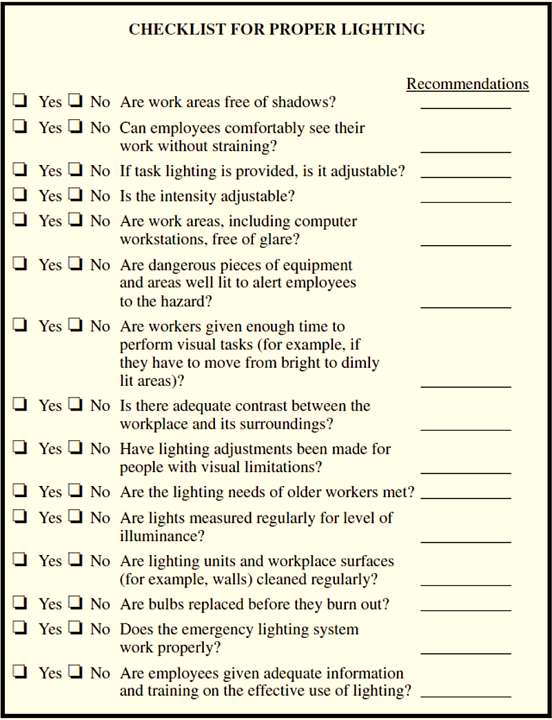

Proper lighting is also required by law. There must be sufficient light in the workplace to ensure the safety of every worker. There must be adequate levels of light to allow workers to perform their tasks in a safe manner as well as backup lighting in an emergency or power failure. To access whether lighting is sufficient in the workplace, consider these factors:

- Human factors.

- Area to be lit.

- The task to be done.

- Equipment and furniture used in tasks (see Figure 1-6).

Also Read: lighting-improves-safety-performance-at-construction-sites-2/

Emergency Lighting

Emergency lighting is required in:

- Exit paths inside office buildings and areas that are two or more stories high.

- Exit paths inside industrial buildings or areas (such as a laboratory or shop).

- Elevators.

Emergency lighting systems must provide one or more foot candles throughout an exit path for at least 1.5 hours after a power outage occurs. Areas without natural light and areas where hazardous operations are conducted must have adequate emergency lighting to permit personnel to exit during an outage (see Figure 1-7).

Emergency lighting may also be installed in areas that may otherwise be hazardous to exit during a power failure. Emergency lighting systems may be either battery- or generator-powered. A maximum delay of 10 seconds is permitted for emergency lighting provided by an electrical generator. Non-generator-powered emergency lights are to be tested monthly.

Indoor Air Quality

Given that the sealed office building is a fact of life for many workers today, office staff depends on smoothly functioning ventilating, air conditioning, and heating systems to maintain the quality of indoor air. These systems keep buildings cool in summer and warm in winter. They bring fresh air in from the outside to help prevent the dangerous buildup of CO2 and vent substances from newly painted walls, new carpets, and new furnishings.

It is important that the quality of this air be controlled by testing and determining temperature, humidity, airflow rates, harmful gases, and substances such as microbes and particulates. Indoor air quality systems must protect workers from pesticide spraying, terrorist attacks using nuclear, biological, or chemical means, and releases from nearby industries or other release sources.

Also Read:photo-of-the-day-indoor-air-quality/

Security

Consider ease of visual and physical surveillance by the residents of areas such as the street, the main entrances to the site and the building, public open space, and parking areas. Consider locating windows from actively used rooms such as common areas, meeting rooms, and lunch rooms so that they look onto key areas. Also consider containing open spaces within the building layout and using the selection and layout of plant materials to enhance, rather than hinder, surveillance and security. Consider specific design strategies to maximize the security of the building, including adequate lighting, lockable gates and doors at all entrances to the site and the buildings, and video cameras and monitors.

Consult with a security expert to ensure that all electrical/electronic security systems are hard-wired and other security measures are installed during the building process to preclude the after-market expenses of having to retrofit the building.

FIRE SAFETY DESIGN

The Life Safety Code (NFPA 101) from the National Fire Protection Association provides minimum requirements for the design, operation, and maintenance of buildings for the safety of life from fire and similar emergencies. The code requires new and existing buildings to allow for “prompt escape” or to provide people with a reasonable degree of safety through other means. Figures 1-8 and 1-9 provide a checklist for the Life Safety Code and hazardous materials.

Also, Read Fire safety for office workers

LIFE SAFETY CODE CHECKLIST

The purpose of the Life Safety Code is to establish minimum requirements that will provide a reasonable degree of safety from fire in buildings and structures. This checklist is provided to assist you in identifying Life Safety Code Violations. Please remember, though you may not be an expert in life safety, your inspection input is important. A little common sense goes a long way. Look around, imagine there was a fire, and look for potential problems. If you’re not sure about something, write it down on this checklist. The following checklist is to be used as a guide. “Yes” indicates compliance and “No” indicates an issue to address.

Department Fire Plan and Evacuation Map

❏ Yes ❏ No Is there a narrative fire plan and does it include the actions to be taken in case of fire? ❏ Yes ❏ No Is there a fire evacuation map and does it include:

❏ Yes ❏ No A sketch of all rooms in the office area?

❏ Yes ❏ No A marking “You are here”?

❏ Yes ❏ No Red arrows show the primary evacuation route and yellow arrows show the secondary route.

❏ Yes ❏ No Identify exterior exits for each route.

NOTE: Evacuation maps are not required in all spaces, only in hallways where exits are not visible or obvious, and areas where the evacuation route is not obvious or is unfamiliar to personnel or visitors.

Monthly Inspection of Fire Extinguishers

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all extinguishers serviceable ensuring that hoses are not cracked, nozzles obstructed, or seal broken?

❏ Yes ❏ No Is the pressure gauge in the operable range?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are Fire Extinguisher Inspection Records Available?

❏ Yes ❏ No Has the extinguisher been checked every month and initialed?

Electrical Systems

❏ Yes ❏ No Are electrical cords in serviceable condition, i.e., not twisted, frayed, spliced, knotted, tacked, or stapled to the wall?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are extension cords not used?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all coffee makers on a nonflammable surface, with a safety check and an authorization to use them in the lunchroom?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are authorized adapters used on electrical plugs?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all personal electrical devices inspected and bearing a safety sticker with the inspector’s initials and date?

Flammable/Combustible Liquids and Gases

❏ Yes ❏ No Are compressed gas cylinders (oxygen, carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, etc.) chained (secured) so as to prevent falling?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are flammable storage cabinets marked “FLAMMABLE MATERIAL”?

❏ Yes ❏ No Do all compressed gas cylinders not in use have a cylinder cap?

Exits

❏ Yes ❏ No Are fire doors propped open?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all exits clearly marked, illuminated and operational?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all exits easily opened?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all hold-open mechanisms in working order and do all doors close entirely?

❏ Yes ❏ No Do all corridors or passageways required for exit access have a 44-inch clear path of travel?

❏ Yes ❏ No Do smoke barrier doors (metal double doors in the main passageways) have a gap of less than 4 inches when closed?

❏ Yes ❏ No Is anything blocking the fire exit doors?

Staff Safety

❏ Yes ❏ No Are precautions taken to insure that floors are clean and clear?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are any wastebaskets constructed of flammable material?

❏ Yes ❏ No Is biohazard waste disposed of in the proper receptacle?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are there any portable heaters in the office area?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are storage areas neat and clean?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are all ceiling tiles in place?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are there any visible stains on ceiling tiles?

❏ Yes ❏ No In sprinkler areas, is material stored closer than 18 inches from the ceiling?

❏ Yes ❏ No Were all new employees briefed on the hazards of their job and action documented?

❏ Yes ❏ No Is eating and drinking prohibited where toxic or infectious wastes are routinely present?

Figure 1-8. Checklist for the Life Safety Code.

Hazardous Materials Checklist

This checklist is required for monthly inspections as part of the life safety inspection for all areas having hazardous materials storage cabinets and rooms. Continue to the end of the checklist if these entries do not apply. “Yes” indicates compliance and “No” indicates an issue to address.

Cabinet

❏ Yes ❏ No In locations where flammable vapors are present, are precautions taken to prevent ignition by eliminating or controlling the sources of ignition?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are storage cabinets designed to limit internal temperatures to a maximum of 325 degrees F when subjected to a 10-minute fire test?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are metal and wooden cabinets designed to meet OSHA and NFPA standards?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are the cabinets in good condition with no cracks, tears, corrosion, or missing parts?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are any liquids or materials leaked onto the shelves?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are the shelves in good condition with no bends or sagging?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are no more than four cabinets stored next to each other?

❏ Yes ❏ No Do the doors close by themselves completely?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are the cabinets properly labeled for the materials stored, e.g., flammables, corrosives, and acids?

❏ Yes ❏ No Do the cabinets contain materials other than the hazardous materials designated for storage? (Example: Tyveks stored with formalin)

❏ Yes ❏ No Is personal protective equipment stored in the cabinets?

Chemicals

❏ Yes ❏ No Do all containers of hazardous materials have readable and non-stained labels?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are the containers stored according to compatibility?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are the lids of the containers secured tightly with no cracks or breaks?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are the containers in good shape with no cracks or broken parts?

❏ Yes ❏ No Do any of the items in the lockers have expired shelf-life dates?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are no more than 5 gallons of Class I or II liquids or 1 gallon of Class III liquids stored in a storage unit locker?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are containers of hazardous materials stored outside the locker?

Spills and Disposal

❏ Yes ❏ No Are spill procedures located in the work area?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are personnel competent in knowing and demonstrating spill procedures?

❏ Yes ❏ No Are personnel knowledgeable in disposal procedures?

Figure 1-9. Hazardous materials checklist.

The Life Safety Code meets its objective by following two parallel approaches. First, it defines hazards, along with general requirements for the means of egress (a path of exit travel to a public way outside), fire protection features (such as fire doors), and building service and fire protection equipment (heating, ventilating, and air conditioning systems, sprinkler systems or fire detection systems, for example). Next, the Life Safety Code sets out life safety requirements that vary with a building’s use. Buildings designed for office use, such as those with office workstations, have distinct life safety requirements compared to facilities like hospitals and schools.

Unique among fire safety codes, the Life Safety Code has different provisions, depending on the type of occupancy and whether the building is new or exist- ing construction. The Life Safety Code can be used in conjunction with a building code or alone in jurisdictions that do not have a building code in place.

The Life Safety Code’s objective is to provide safety to life during emergencies. However, two additional very positive spin-offs grew out of this objective.

- Many requirements that are designed to protect people also protect property, reducing the dollar’s loss associated with fire.

- Requirements that are designed to provide “prompt escape” during emergencies make buildings more pleasant during normal conditions. Spacious corridors and the convenience of multiple exits, for example, result from the requirement for “prompt escape.”

The Life Safety Code requires unlocked and unobstructed exits, multiple exits, fire doors, and regular fire exit drills. These key provisions state:

- Locks and hardware on doors shall be installed to permit free escape.

- Exits must be marked with a sign that is readily visible.

- Any door in a means of egress must be capable of swinging from any direction to the full use of the opening. The door must swing in the direction of egress when serving a room or area with 50 or more occupants.

- Evacuation signals must be audible and visible.

INTERIOR DESIGN

Interior design can be viewed very narrowly or very broadly. It is more than aesthetics related to the beautification of the office building. It is an approach that looks for potential hazards and makes sure that you are not building in hazards or bringing hazards into the office work environment. Also, it considers safety during the purchasing process. This may seem simple but it does take a concerted effort to make it a priority. The cheapest is not always the safest and healthiest.

The interior of the building must be designed to be free of hazards as much as feasibly possible. Such items as the following must be part of the interior design:

- Safety glass for door and walls.

- No protrusions into walkways, offices, corridors, etc.

- Non-skid surfaces as much as possible.

- No access to an exposed electrical circuit.

- Cover over all lights.

- Use of ramps for the handicapped or disabled.

- Non- allergenic materials for walls, floors, ceilings, furniture, windows, etc.

- Walls, shelves, and dividers are securely anchored.

- Fall hazards are guarded by rails or other means.

- No sharp edges.

- Handicapped hygiene facilities.

- GFCIs guard electrical circuitry near water sources.

- Adequate numbers of electrical receptacles.

Also Read: Five Steps to Improve Ergonomics in the Office

FURNISHINGS

Since most of the office staff will be using and surrounded by the furnishings, the purchasing and procurement of all office furniture should be undertaken with use, safety, and health in mind. Making sure the office furniture will support its use by office staff is important. It should be constructed with industrial use in mind. It will receive more wear and tear than most furniture in one’s home. (See Figure 1-10).

You should be aware of the following aspects regarding furniture:

- Does it meet strength requirements?

- Are there sharp corners, glass tops, or protruding parts that create hazards?

- Are chairs designed for their intended purpose, e.g., desk chairs, meet- ing room chairs, computer workstation chairs? For example, computer workstation chairs should have five legs to help prevent upsets.

- Are shelves and file cabinets stable for the loads?

- Is the furniture comfortable since workers will be using it daily? It should not facilitate possible stress-related injuries such as repetitive motion injuries.

- Do all moving parts of furniture move free without binding?

- Is all furniture functional in this office environment?

CONTRACTOR SAFETY

A part of designing for safety and health is the hiring of contractors to complete work or to provide service regarding your office building. This process should not be viewed as easy or unrelated to safety and health. Far from this, safety and health are equally as important as is the contractor’s skill to do the work for which you are contracting.

Pre-qualification

It is very necessary to pre-qualify all potential contractors who have to submit a bid to do your scope of work. You must determine if the contractor can carry out the job safely. This is done by evaluating the contractor’s performance and competency. Some of the criteria to consider are:

- What is the nature of the work (location, type of activity, time scale for completion, number of contractors on the site, etc.)?

- What financial costs are involved?

- What hazards are currently identified on the site or may be introduced during the project?

- Are there existing drawings and what relevant information do they show?

- Are there site-wide factors to be considered (sit access and exit, loading/ unloading areas, exclusion of pedestrians, or specific rules of operation from yourself)?

During this pre-qualification process, it is important to determine the performance record of the contractor and the use of best management practices. As a part of performance, safety and health performance should be evaluated. Some of the factors to take into consideration are:

- Is the contractor’s experience modification rate (EMR) for workers’ compensation equal to or less than 1? You should hire no contractor with an EMR above 1.

- Request a history of the contractor’s OSHA recordable cases.

- Request or obtain from the OSHA website a history of the contractor’s OSHA violations.

- Compare the contractor’s incident rate with that from the BLS for his SIC code.

Some questions that you should have answered are:

- Does the contractor have a written safety and health program?

- Has the contractor implemented his or her safety and health program?

- Is the contractor’s senior management committed to the safety and health initiative?

- Has the contractor assigned a particular person the responsibility for safety and health on the job or project sites?

- Are supervisors held financially accountable for the safety and health of their crews?

- Are safety and health visible and an integral part of the contractor’s other projects?

- Are all the contractor’s employees trained in safety and health and the expected job hazards? Is this training documented?

- Does the contractor work to improve safety and health on his or her job site?

Contractor-Management Responsibilities

Specifically for construction activities the following regulations state rather clearly what the contractor’s responsibility is regarding safety and health on the job site:

- 29 CFR 1926.16(a), OSHA regulation states, “In no case shall the prime contractor be relieved of overall responsibility for compliance with the requirements of this part for all work to be performed under the contract.”

- 29 CFR 1926.16(c), OSHA regulations further state, “With respect to subcontractor work, the prime contractor and any subcontractors shall be deemed to have joint responsibility.”

- 29 CFR 1926.16(d), “Where joint responsibility exists both the prime contractor and his subcontractor or subcontractors, regardless of their tier, shall be considered subject to the enforcement of provisions of the OSHAct.”

Training

Safety and health training is one way of trying to ensure that workers and their supervisors are cognizant of safety and health expectations as well as the site-specific hazards involved in your office building.

- Contractors have the responsibility to ensure that all employees are properly trained.

- Safety orientation should include a review of:

- Physical and chemical hazards on site (fire, explosion, and toxic release type hazards).

- General safety rules and regulations.

- Work permit procedures.

- Other day-to-day issues.

- Training will raise the level of safety awareness.

Other Steps to Ensure Safety and Health

It is essential to prevent and reduce injuries and illnesses and maintain a safe work environment for workers of contractors. Relevant to safety and health, everything that is done should be designed to protect employees, the company’s facilities, and the local community. You should make sure that the following are accomplished in order to preserve safety and health in contract-related work. Some of what you might undertake are:

- Conduct a pre-entry briefing prior to site entry and at other times, as necessary, to ensure employees are aware of site hazards.

- Job hazard analysis techniques can be used to develop project or job specifications and procedures by:

- Reviewing the scope of work.

- Identifying and evaluating controls for reducing hazards.

- Reviewing hazards of each task such as:

- Biological hazards.

- Fall hazards.

- Electrical hazards.

- Overhead/underground utilities.

- Heavy equipment.

- Lockout/tagout.

- Chemical hazards.

- Permit-required confined space.

- Barricading and fencing.

- Asbestos and lead.

- Hot work permits.

- Scaffolding and ladder hazards.

- Trenching and excavations.

- Periodic safety inspections and the correction of any deficiencies.

- Documentation of the planned work should be maintained at the workplace.

- Any changes should be documented, reviewed, and updated as necessary.

The Agreement

As a part of the contract, you should include a safety and health agreement.

As part of this agreement, you should include:

- Details of the responsibilities of the contractor and yourself regarding safety and health.

- Contractor’s proof of an existing and functional safety and health program.

- Details of any specific hazards that may be relevant to the contract work and provided to the contractor.

- The contractor should provide details of any hazards that it will bring onto the site or workplace or any hazard that may be created as a result of the nature of the work undertaken and the safety guards that will be imposed to mitigate the hazard to the greatest extent possible.

- Assurance that the contractor’s employees have received the safety train- ing required for the specific job.

- Emergency and personal protective equipment are available by the contractor.

- The contractor will be advised on miscellaneous matters, such as how to activate the fire alarm, the location of fire extinguishers and first aid assistance, escape possibilities, and where and to whom the contractor should report in case of an emergency situation.

- Strategies for communicating issues related to safety and health (e.g., site meetings)

Evaluation

You must develop guidelines for contractors. These include your policies and procedures as well as contractor safety rules and procedures regarding safety and health. You must learn about mistakes and near misses as part of the learning and prevention process. You must measure and monitor the contractor’s safety and health performance.

This is accomplished by tracking accidents, incidents, equipment damage, recordable injuries or illnesses, and even first aid cases. Conduct surprise inspections to determine the contractor’s attitude toward job safety and his or her desire to improve performance. It is important to develop a measurement of safety and health performance.

Contractors must have an on-site project manager or supervisor for essential smooth and efficient operation. Contractors and their managers must share the overall responsibility and liability. Contractors and their managers must be professional and able to interpret and manage safety programs and solve problems efficiently and expediently. Contractors and their managers must have or develop the skill to handle legal, financial, and customer relations. A contractor’s safety program is a catalyst for reducing accidents. You should not accept a minimal or “paper” safety program. You want contractors to commit to excellence in safety and quality practices. Without safety, you can expect poor quality and this poor quality leads to increased pro- duction costs and poor employee morale. Contractor safety and health performance is the key to getting what you are paying for.

Also Read: https://hsseworld.com/photo-of-the-day-ergonomic-chair-and-office-chair-safety-tips/

For more safety Resources Please Visit Safetybagresources